Dark and Stormy

January 31 2026

I’m especially proud of this: I wrote a paper on sentences from the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest(BLFC). I don’t recall how I found the BLFC, but I knew these sentences were too good to not study further. All credit to Scott and EJ Rice for organizing this wonderful contest for many, many years, and graciously giving me permission to study the resource they curated.

As it turns out, just having data isn’t enough to get a paper out. Neither is having fun ideas about how you’d analyze it. Working on it for months on end despite multiple dead-ends, and finding a wonderful collaborator in Laura were key to finishing this paper. I hope people find the resource and paper interesting, and a jumping-off point for further work!

One of my favorite analyses in the paper is the final section, where we look at ‘deviant’ adjective-noun (AN) bigrams. Deviancy is hard to define, but it arises when a phrase is grammatically well formed but the overall meaning is weird or incongruent (colorless green, residential steak, warm equation) The term is from a 2016 paper by Eva M. Vecchi where they collect paired acceptability judgements for about 25K ANs, building distributional models that predict deviancy extremely well.

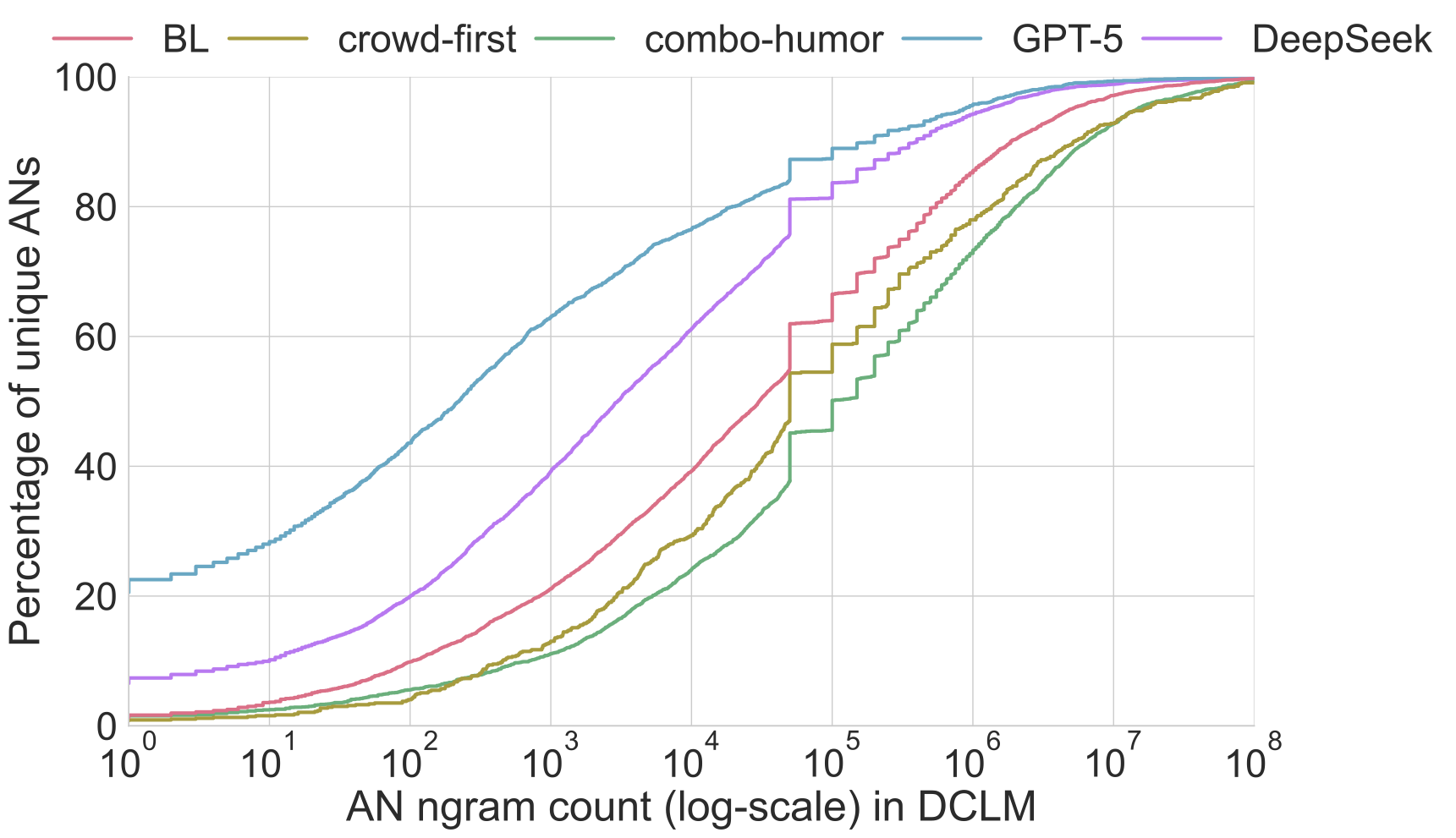

We found that Bulwer-Lytton sentences contain many more deviant ANs than control sentences (from openings to novels and humor datasets). What was surprising was that LLM generated Bulwer-Lytton sentences contain even more deviant ANs compared to BLFC entries. To derive the count of AN bigrams, I used the excellent infini-gram API to query the DCLM pre-training corpus containing over 3 trillion words. Figure 5 from our paper shows this effect beautifully: the BLFC corpus contains many more rare/deviant ANs than control sentences. Further, 80% of ANs generated by DeepSeek occurred less than 1000 times in the DCLM corpus, compared to 40% of ANs in the BLFC corpus, and 25-30% in control.

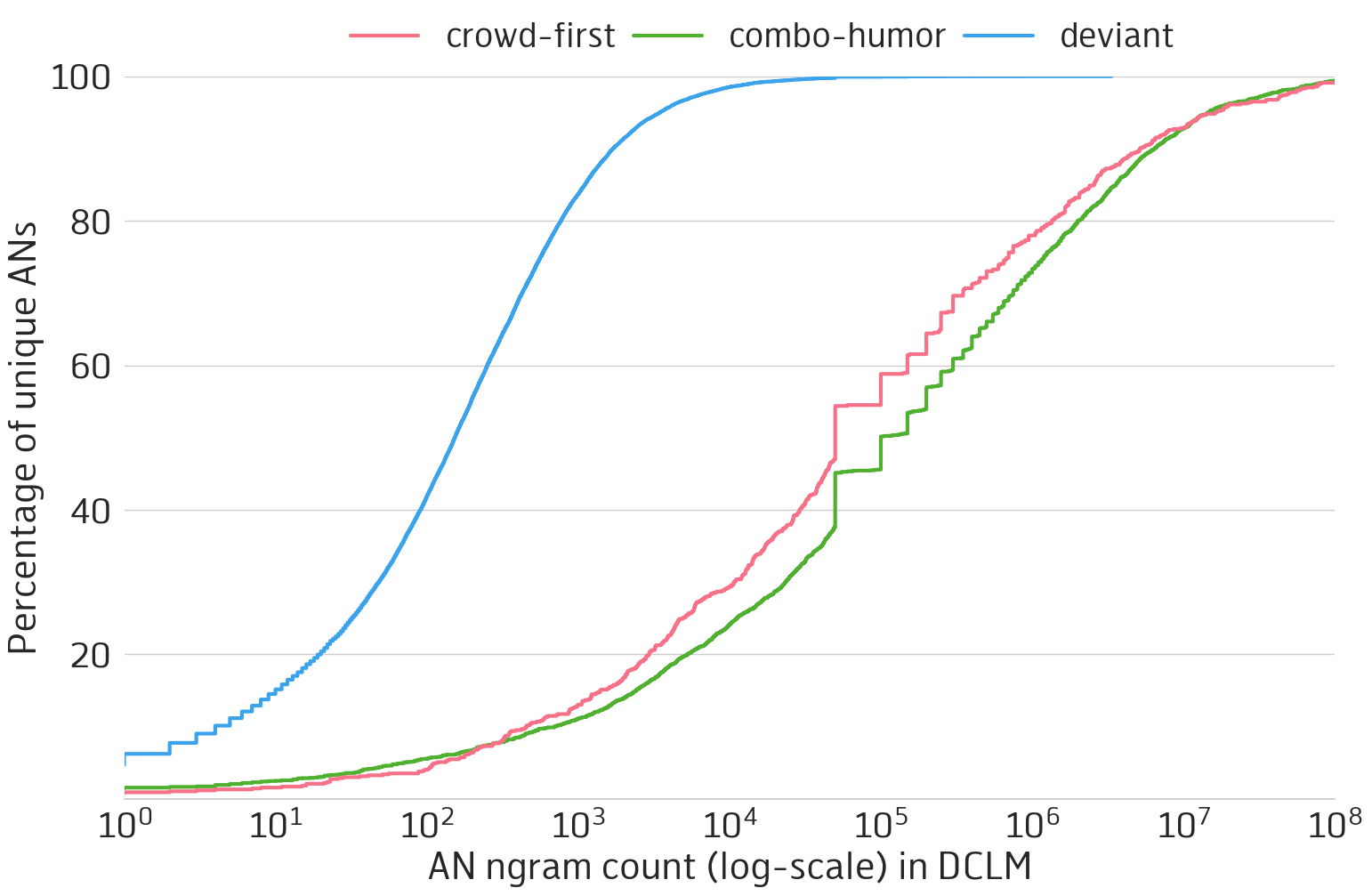

This got me thinking back to Eva M. Vecchi’s original dataset of deviant ANs. They quantified these ANs as unattested by looking at a corpus of 3 billion words— tiny by the standards of today’s pre-training corpora. What if we query their count against the DCLM pre-training corpus? The figure below validates that most of these ANs are indeed, deviant. 80% of them occur less than 1000 times in the corpus.

My counting methodology isn’t perfect. infini-gram just queries raw strings, so some entries are over/under-counted for various reasons: misspellings, polysemy (meaning its not really an adjective-noun bigram), a missing prefix/suffix, etc. But I don’t think it takes away from the story these figures tell. Then I got another idea with all the deviant ANs I had at my disposal.

So here it is — a webpage that gives you a random deviant adjective noun bigram (I filtered the list down to 3994 ANs that occured less than 10 times in the DCLM corpus). Here are some of my favorites from randomly reloading the page: bold airfield, classical bowler, informal fate, nuclear suitability.

Punching Bag

December 26 2025

This is going to be another post reminiscing on the past, and my present self possibly assigning too much meaning to an incident that’s wedged in my brain. My English teacher in 9th or 10th standard wrote ‘Punching Bag’ on the blackboard and asked all of us to come forward and write what came to mind when we read the phrase. I forgot what I wrote, but everyone made literal connections like ‘boxing’. Maybe someone wrote ‘anger’. Then she went to the board and wrote ‘Mother’.

I’ve been meaning to blog my thoughts on this memory for months, but I have a renewed interest as I make the decision to choose whom I love and marry despite my mother (and father’s) disapproval. As the emotional manipulation, blackmail and abuse reaches the worst it’s ever been, I try to remember to not treat my mother as a punching bag. Not for the reason my teacher intended (to always show grace for mothers despite abuse), but because I need to grow and flourish mentally. I understand how my mother is a product of a traumatic society and politics, but socio-political understanding can’t solve personal problems. The personal is political, but solving interpersonal conflict requires people to reflect and change. My mother can’t do that because she doesn’t want to.

A few weeks ago, Sohla El-Waylly blogged about her experiences being labelled difficult at work, and I cried reading about her upbringing:

I grew up in an extremely conservative family and only interacted with a limited group of people with similar views until I reached adulthood. My life was small and secluded. They were all immigrants from Bangladesh, away from their families and homes in a new, often hostile, country. They did what they thought was protecting us, demanding full control over their children. I never handled it well…It’s an uneasy thing believing that your mother will only love you if you do what she wants. When my parents found out I had a boyfriend in college, they stood outside my dorm room on their knees, crying and screaming, hollering my name…My mother was so embarrassed by my divorce that on my wedding day to Ham she apologized to his father for having to take me, this difficult girl, into his family.

She understands why her family behaved the way they did, doesn’t excuse it, and marches on. I don’t know how she does it, but I have to as well. Accept that my parents won’t change, will continue to manipulate and hurt me, and that I need to maintain my sanity and try to be there for them as a son. Somehow.

FizzBuzzing LLMs

December 11 2025

Tom Scott’s video explaining why FizzBuzz is a good interview question to weed out bad programmers is 8 years old (!) and still a great watch. I figured it would be a fun exercise to study how various LLMs solve the problem for the same reason Tom says in the video: it reveals one’s coding style. Do they bodge a solution together? Or do they plan and think long-term?

Here’s the FizzBuzz problem statement (from a blogpost by Imran Ghory that Tom cites in his video), that I used verbatim when prompting:

Write a program that prints the numbers from 1 to 100. But for multiples of three print “Fizz” instead of the number and for the multiples of five print “Buzz”. For numbers which are multiples of both three and five print “FizzBuzz”.

I ran all of the prompts in the first week of December 2025, and include links to the full chat when possible.

GPT-5.1

for i in range(1, 101):

if i % 15 == 0:

print("FizzBuzz")

elif i % 3 == 0:

print("Fizz")

elif i % 5 == 0:

print("Buzz")

else:

print(i)

This is probably what I would write in response to the question. It’s a decent solution, and probably represents the average programmer’s answer to the question. I like that its clean with no comments; There’s no statement or expression so complex that needs explaining here.

Gemini 3

def fizzbuzz(n_max):

"""

Prints numbers from 1 up to n_max, with substitutions for multiples

of 3 ("Fizz"), 5 ("Buzz"), and both ("FizzBuzz").

Args:

n_max (int): The maximum number in the range (inclusive).

"""

print(f"--- FizzBuzz sequence up to {n_max} ---")

# Loop from 1 up to and including n_max

for n in range(1, n_max + 1):

output = ""

# Check for multiples of 3

if n % 3 == 0:

output += "Fizz"

# Check for multiples of 5

if n % 5 == 0:

output += "Buzz"

# If output is still empty, it means n is not a multiple of 3 or 5,

# so we print the number itself.

if not output:

print(n)

else:

# If output has "Fizz", "Buzz", or "FizzBuzz", print the string.

print(output)

# Run the function for the required range (1 to 100)

fizzbuzz(100)

I didn’t ask for a function, but Gemini wrote one anyway. Google seems to have focused on training Gemini models (since at least 2.5) to always output code that’s extremely well-commented. I’m surprised there aren’t type hints1 and emoji sprinkled all over the comments and print statements, but I guess it reserves that behavior for more complex coding challenges. Both of these are almost certainly behaviors the model ‘learns’ during human-preference alignment: annotators/users just prefer responses with emojis and lots of comments. I don’t.

It did use string concatenation to solve FizzBuzz though, which is a smarter way to solve the problem over if-elif-elif-else.

Claude 4.5

Claude Haiku used string concatenation and was thankfully less verbose like GPT-5.1:

for i in range(1, 101):

output = ""

if i % 3 == 0:

output += "Fizz"

if i % 5 == 0:

output += "Buzz"

if output == "":

output = str(i)

print(output)

Claude Sonnet, despite being the larger, smarter model, chose to solve the problem using if-elif-elif-else:

for i in range(1, 101):

if i % 3 == 0 and i % 5 == 0:

print("FizzBuzz")

elif i % 3 == 0:

print("Fizz")

...

The responses from GPT-5.1 and Claude were short and plain, and I prefer them both to Gemini. However, both these models do write extensive comments (and emoji) when they are tasked with bigger coding challenges, which is smart product design on OpenAI and Anthropic’s part.

DeepSeek-V3.2

DeepSeek-V3.2 gave me 3 different solutions. A solution using if-elif-elif-else, another using string concatenation, and this one-liner:

for i in range(1, 101): print("Fizz"*(i%3==0) + "Buzz"*(i%5==0) or i)

I hate one-liners and code that’s trying to be too cute or smart, but I’ll excuse this. Barely. Multiplying a boolean with a string and then taking inclusive or with an integer… I think this is Python’s fault for allowing such a monstrosity.

What did I learn?

A student in my introductory Python class asked if there were any accuracy differences for code generated by different AIs, and I said no, but there were differences in style. After this little exercise and more experience with coding agents, I’m not sure style is the right word. The code samples above are stylistically different, but the differences come from design decisions by the companies to boost engagement.

Gemini adds extensive comments because Google thinks you’ll like that code more and it will get you to use Gemini more. DeepSeek generates 3 solutions probably for the same reason. Claude and GPT-5.1 are more adaptive in their responses, but they exhibit similar engagement boosting tactics2. Ultimately, I think this exercise gives a peek into what the latest LLMs from these companies actually are: products designed with the purpose of increasing ‘engagement’. They just want us to keep using them.

Update: I took it one step further and made a benchmark out of LLMs playing FizzBuzz. Some mildly interesting results!

-

Type hints in python don’t do much. ↩

-

ChatGPT almost always ends its response with a follow-up question, or a cheery sentence about how it can do something else. Genius, but also insidious. ↩

Levels of nuance never reached

September 20 2025

I’ve finally published a paper where I could cite KJ Healy’s provocative 2012 paper ‘Fuck Nuance’. It’s not the most technically sophisticated paper I’ve worked on, nor the most intellectually interesting, but as soon as I saw all those papers about ‘fine-grained’ synthetic personas, I knew that this was probably an instance of researchers falling into the ‘fine-grained nuance trap’ and that I needed to look into it with my collaborators Chantal and Gauri. Our findings aren’t conclusive across all models and settings, but in our specific experimental conditions fine-grained detail in personas don’t dramatically improve the lexical diversity of synthetic data from LLMs.

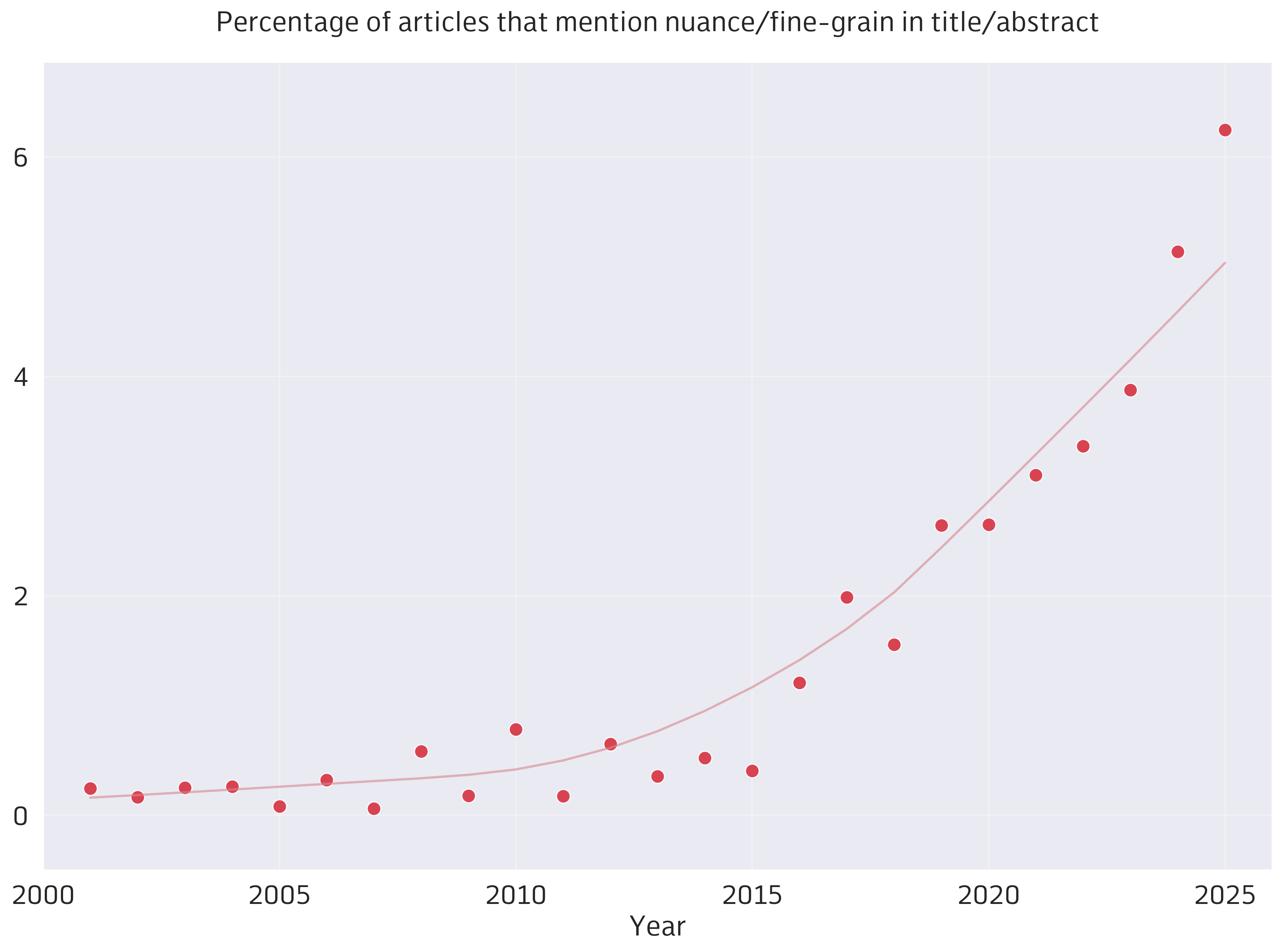

The paper is a short read, I hope some people find value in it. But I wanted to use the paper as an excuse to revisit my very first post on this blog. It’s been five years, has the phenomenon of nuance rising slowed down in ACL publications?

Nope. At the current rate of doubling, over half the papers published in *CL venues will mention nuance/fine-grain by 2040! I can’t wait to write the follow-up to this post in 2030 to see if we’ve reached peak nuance.

Again, I don’t hold a value judgement one way or another and at least 2 of my articles contribute to this phenomenon. I think words like ‘nuance’ and ‘fine-grain’ are just words we attribute high value to as researchers and use even when we don’t need to or have to. Words also fall into and out of style — but I do think a lot of us also fall into the nuance trap when we study research questions to make our papers sound more appealing.

Kural embeddings

August 23 2025

Over the last two years, I’ve seen quite a lot of blog posts, videos and explainers about embeddings which initially surprised me. It shouldn’t have, since ‘AI’/LLMs are everywhere now; Developers, students and hobbyists are really excited (as I assume they were about the Web in late 90s/early 2000s and mobile apps in the early 2010s) to understand them and build something using them. Still, it feel surreal for the concept I studied as a Masters student to be the focus of attention for the whole computing industry. There’s too much attention and hype, and I do wonder (with some fear) what a massive financial bubble bursting actually looks like at the micro level in everyday life.

One undeniable positive to come from all the hype around ‘AI’ is much better developer tooling and frameworks for embeddings and neural networks now than in 2017. With Qwen3 multilingual embeddings and Gemini CLI1, I could quickly prototype the first idea that popped in my head: Build a web app that uses a multilingual embedding model to find relevant Thirukural couplets (in Tamil) for user queries in any language. That’s what ‘Kural for your question’ is. I’m pretty happy with the end product, but the retrieval of relevant kural couplets itself with cosine similarity of embeddings is pretty underwhelming.

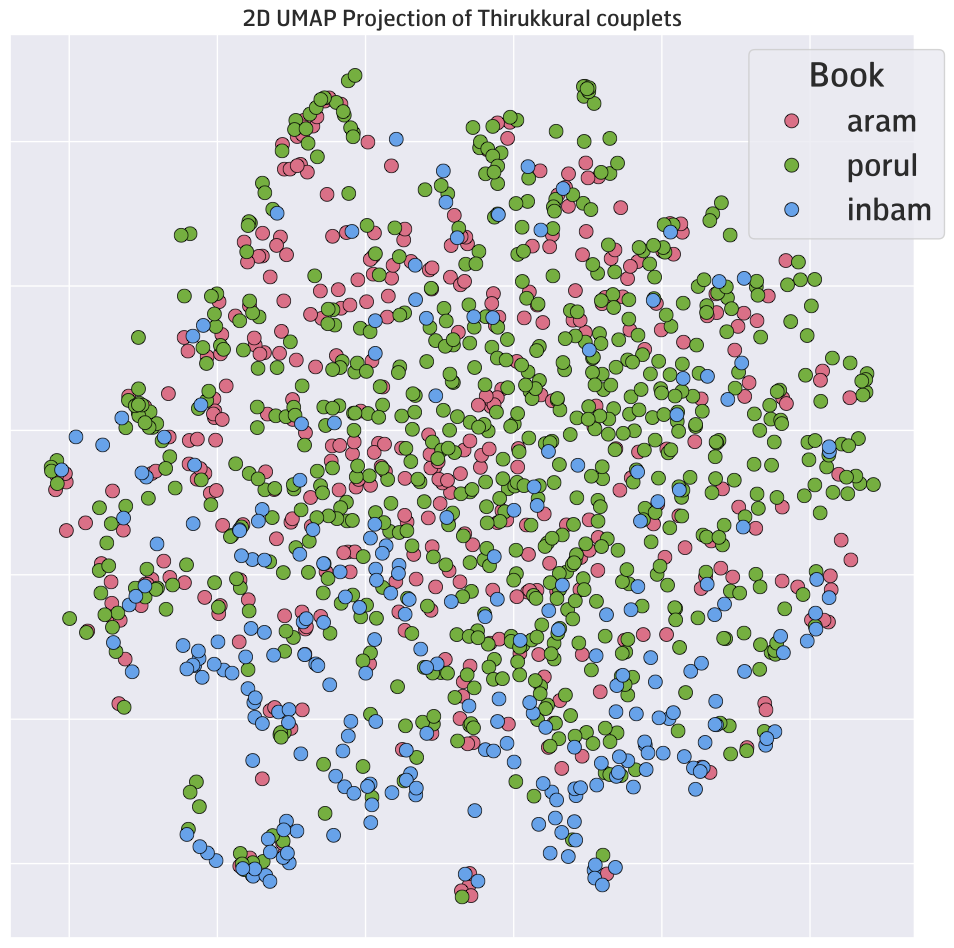

Visualizing the embeddings of all 1330 kurals in 2D using UMAP gives an idea why. There aren’t really any meaningful clusters, with only the Book of Love showing some clear separation from the other two books. The similarity search works sometimes because of certain key words, but lacks any understanding of the intent of the question. For the question What are the duties of a son to his parents? (an undying question for me), only one of the 3 kurals deemed relevant is about the parent-child relationship at all. The larger Qwen3 embedding models might work better, but model training frameworks and data mixtures are more biased towards real-world use cases — my niche, little idea probably doesn’t mesh well with what Qwen3 Embedding was trained to do.

Still feels good to build something, even if underwhelming 🙂.

-

Just like Typeproof — I know its dangerous, but boy is it addictive to build fully functional web apps with just text prompts. I’ve learned more Typescript this way than I have in years, but not as much as I would have learned if I had built these apps from scratch. But I would have never built these web apps from scratch either. ↩